Queues in software development

Queues are well known structures to most programmers. They are covered in most introductory courses on data structures, are a part of the standard libraries of most - if not all, languages that are widely used in the industry.

A queue is a structure that implements FIFO ordering on its constituent elements. The formal study of queues is called queuing theory. Apart from FIFO ordering, two other properties that are interesting are average waiting time and average length of the queue.

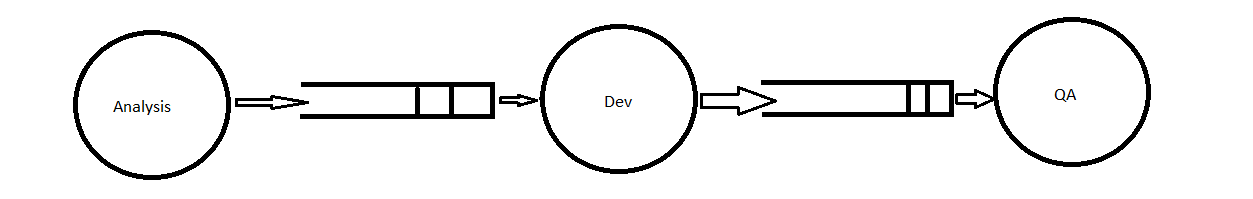

In a typical software development workflow, tasks flow through one of the following activities

- Analysis

- Development

- QA

- Acceptance test

- Release

We can model the development workflow as a sequence of processes one for each activity. A task then becomes a unit of work that flows from one process to the next. People working on the task contribute capacity to the process. In an ideal scenario, each process would have exactly the right amount of capacity at exactly the right time to handle the tasks. But in most cases, the amount of capacity needed to perform the tasks is greater than the amount of capacity available. So inevitably, inputs to the processes get queued up. It is important to note that in a software development workflow, work not only flows forward, but also in certain cases, backward. If a bug is found by the QA, the task naturally moves back into the development queue.

This model of a software development workflow provides a structure with which we can reason about the following well known observations.

- Estimating how long even a simple task would take is a hard problem

- The latency and throughput of the development workflow is limited by slowest activity

- Typing speed is not the bottleneck for any serious development process

- Defects should be fixed before new development can take place

- Knowledge silos are bad for the effectiveness of the process

Lets dissect them further.

Estimating how long even a simple task would take is a hard problem

This is fairly obvious to prove using the queuing model. The total time for the completion of a task is the actual time spent working on the task, plus the time for which the task is waiting in one of the queues. We can at this point, go ahead and do a statistical analysis on the queues to calculate the average waiting times and there by calculate the total time; but one should question the usefulness of such an approach.

The latency and throughput of the development workflow is limited by slowest activity

This is also a fairly obvious conclusion. If the QA process is limiting the throughput, it does not make sense to hire developers. But this is exactly what happens in many real world scenarios. The distinction becomes even more obscure when analysis is the limiting the throughput. Incompletely analyzed tasks are moved into the development queue which reduces the throughput of the development process and this leads to hiring more developers. All these underscore the importance of having structured feedback without which we could be solving all the wrong problems.

Typing speed is not the bottleneck for any serious development process

The limiting factor in a software development process is not stationary. If one bottle neck is removed, another emerges. This is true for any queuing system as there exist at least one bottleneck in any queue. Too often, people engage in micro optimizations like choosing a language which has a less verbose syntax. They may or may not be the bottleneck of the system. Care should be taken to address the immediate bottlenecks prior to addressing potential ones down the line.

Defects should be fixed before new development can take place

A version of a software system that has defects is usually not considered for shipment. Developing new features on top of a version that is known to have defects increase the probability of finding regression defects later on. This decreases the throughput of development. In reality, defects do happen and tasks do get stalled. There are two ways in which we can limit the number of tasks that get blocked

- By making sure that the path in which the defect exists does not get executed using toggles

- By breaking the system down into independently verifiable modules.

This way, only the development tasks that affect the path/module where the defect was found are impacted.

Knowledge silos are bad for the effectiveness of the process

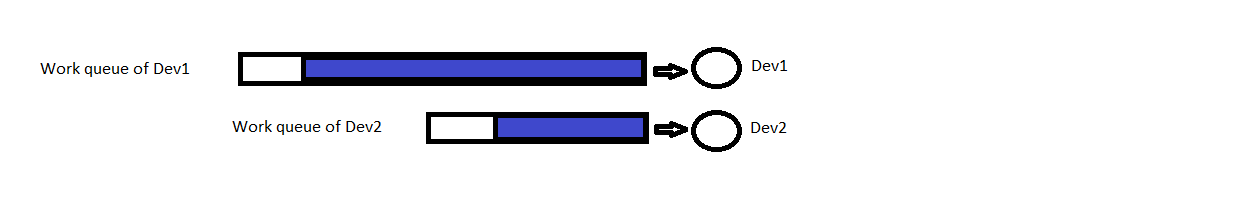

Knowledge silos exist when a limited number of people on the team monopolize knowledge about a particular area. In an ideal development process any member of the team should be able to work on any task. Why because, a team in that state is the easiest to scale. When knowledge silos exist in the team, the throughput of the development process is not limited by the number of developers, but by the amount of work a developer with the largest chunk of work can deliver. Consider the following picture

In this case, it is obvious that Dev1 is monopolizing knowledge about a portion of the system and hence the load cannot be shared between the two developers. Hence the capacity of Dev1 forms a bottleneck in the system. Adding resources to share the load of Dev2 does not have a great impact on the throughput of the system as a whole and adding resources to share the load of Dev1 may be counter productive because in that case, the actual capacity of Dev1 is reduced due to the additional task of having to transfer context to the new person.

Silos are counter-productive for another reason. Developers have an incentive to reduce the size of their work queues as much as possible. This might act as a negative pressure for refactoring and feedback depending upon the nature of the developer as a person. Sometimes the negative pressure might be good as it forces the developer to stay focused and ignore un-necessary refactoring effort. But in my opinion, that should be the call of two or more developers who have second degree exposure to the code in question.

There are many reasons why silos exist. The most natural reason is expertise in the subject. The second most common reason is unknowns. Both of these can be addressed by breaking down the task into smaller well-defined tasks. Doing so serves two purposes.

- It limits the amount of context that should be transferred in one shot

- Well defined closures tend to result in a reduction in the number of defects found. This is because, when the scope of a task is small, edge cases can be identified earlier in the lifecycle rather than later. All this will lead to an increase in the throughput of the system as a whole.

While the results defined here may be true, it is perfectly natural that in a real world software development process there may be more urgent factors that forces you to de-prioritize counter-measures to some of the above problems. The objective of this post was to present a model which you can use can use to reason about the impact of such trade-offs that you may have to make. The silver bullet solution for any software development effort is identifying the problems that you are willing to live with.